Pennsylvania Medical Malpractice Statute of Limitations: A Comprehensive Legal Treatise

A comprehensive guide to PA's medical malpractice statute of limitations. Learn about the standard two-year deadline, discovery rule ex...

Wills vs. Living Trusts: An exhaustive legal analysis. Compare probate costs, privacy benefits, and learn how to fund your estate plan using quitclaim deeds.

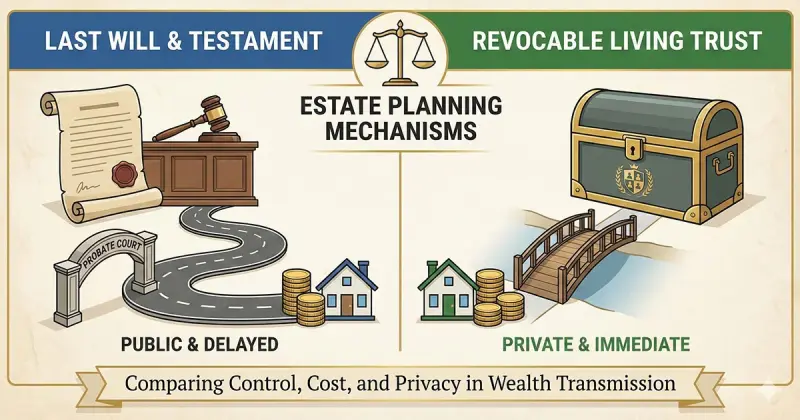

The transmission of wealth from one generation to the next constitutes a fundamental pillar of economic stability and familial continuity. In the United States, this process is governed by a complex interplay of state statutes, common law principles, and tax regulations. At the heart of this system lie two primary legal instruments: the Last Will and Testament and the Revocable Living Trust. While often perceived by the lay public as interchangeable administrative formalities, these documents represent profoundly different legal theories regarding the nature of property, the timing of title transfer, and the role of judicial oversight.

The selection between a will and a trust is not merely a matter of preference; it is a strategic decision that dictates the procedural reality for a decedent’s heirs. A will serves as a set of instructions for the probate court, activating only upon death to guide a public, judge-supervised distribution of assets. In contrast, a living trust functions as a private legal entity created during the grantor’s lifetime, capable of holding title to assets and ensuring their seamless management through incapacity and death without judicial intervention.

This report provides a comprehensive, expert-level examination of these instruments. It explores their historical origins, procedural mechanics, and economic implications. Furthermore, it integrates a detailed analysis of the "funding" process—specifically the use of quitclaim deeds—and examines the evolving landscape of legal service delivery, from traditional hourly billing to modern subscription models like LegalShield. By synthesizing data from legal scholarship, financial analysis, and practitioner reviews, this document aims to serve as a definitive resource for understanding the nuances of estate planning.

To understand the value of a will or trust, one must first comprehend the alternative: Intestacy. When an individual dies without an estate plan, they are deemed "intestate." In this scenario, the state effectively writes a will for them. Every state has a statutory scheme of descent and distribution that dictates who inherits assets based on rigid familial hierarchies.

Intestacy laws generally prioritize spouses and children, but the specifics can lead to unintended and often disastrous consequences. For example, in some jurisdictions, if a person dies leaving a spouse and children from a prior marriage, the assets may be split between them in a way that leaves the surviving spouse with insufficient funds to maintain the marital home. If a decedent has no spouse or children, assets may flow to distant relatives (parents, siblings, cousins) whom the decedent may have had no intention of benefiting. This rigid statutory distribution strips the individual of the autonomy to direct their legacy, forfeiting control to the generic preferences of the legislature.

Beyond the loss of control, intestacy invariably triggers a full probate administration. The court must appoint an administrator (similar to an executor), who must post a bond and navigate the same bureaucratic hurdles as a probate with a will. This process underscores the primary function of estate planning: to opt out of the state’s default plan in favor of a private, customized directive.

The Last Will and Testament is the most recognizable instrument in estate planning. Historically rooted in the English Statute of Wills (1540), which granted landowners the right to devise property that would otherwise pass by primogeniture, the will remains a statutory creation. It is a formal legal declaration of a person's intentions concerning the disposition of their property, valid only after death.

A will is legally described as "ambulatory," meaning it can be changed at any time before death, and "testamentary," meaning it has no legal effect until the testator dies. During the testator’s life, a will conveys no interest to beneficiaries and restricts no assets.

For a will to be enforceable, it must meet strict formalities designed to prevent fraud and ensure "testamentary capacity":

Writing: Nuncupative (oral) wills are rarely recognized; the standard is a written document.

Signature: The testator must sign the document, typically at the end, to prevent additions.

Witnesses: Most states require two disinterested witnesses to attest that the testator appeared to be of sound mind and acting without duress.

Failure to adhere to these formalities can result in the will being declared invalid, reverting the estate to intestacy. This fragility is a key characteristic of wills; because the testator is not present to defend the document during administration, the courts enforce strict adherence to protocol.

A common misconception is that having a will avoids probate. This is factually incorrect. A will guarantees probate. Probate is the legal process of proving the will’s validity and executing its terms under court supervision.

The probate process is a linear, bureaucratic sequence that transforms a decedent's assets into a distributable form.

Filing the Petition: The named executor must file the original will and a petition for probate with the appropriate court. This makes the will a matter of public record, accessible to anyone.

Admission and Letters Testamentary: The court reviews the will. If valid, it issues "Letters Testamentary," a legal document empowering the executor to act for the estate. Until this document is issued, assets are often frozen—a period that can last weeks or months.

Notice to Creditors: The executor must publish notice of the death to allow creditors to file claims. This statutory period (e.g., four months in many states) creates a mandatory delay in distribution.

Inventory and Appraisal: A comprehensive list of assets and their values must be filed with the court. In some jurisdictions, court-appointed appraisers take a percentage fee to value assets, adding to the cost.

Final Accounting and Distribution: Only after debts are paid and tax returns filed can the executor petition the court for permission to distribute the remaining assets to beneficiaries.

The reliance on judicial oversight makes probate an expensive and time-consuming mechanism.

Time: The process typically spans 9 to 24 months. During this interim, beneficiaries may be denied access to funds needed for living expenses or tuition.

Cost: Probate fees are often substantial. In states like California, statutory fees for attorneys and executors are calculated on the gross value of the estate. For an estate with a gross value of $500,000, statutory fees can easily exceed $25,000, regardless of the net equity or the complexity of the work.2

Publicity: The public nature of probate exposes the family’s financial affairs to data brokers, scammers, and prying neighbors. The inventory reveals exactly what was owned and who received it.

Despite its inefficiencies regarding asset transfer, the will possesses a singular, non-delegable power: the nomination of guardians for minor children. A trust, being a property arrangement, cannot speak to the custody of a child. Only a will can formally nominate a guardian to the court. For parents of minor children, this function alone makes a will a mandatory component of an estate plan, even if a trust is used for assets.

The Revocable Living Trust (RLT) has emerged as the preferred instrument for comprehensive estate planning, particularly for those with real estate or significant assets. Unlike the will, which is a creature of statute, the trust is a creature of contract and equity. It separates the legal title of property (held by the Trustee) from the equitable title (enjoyed by the Beneficiary).

An RLT is established by a written agreement (the Declaration of Trust) during the grantor's lifetime.

The Trinity of Roles: The trust involves a Grantor (creator), a Trustee (manager), and a Beneficiary (recipient). In a typical RLT, the Grantor fills all three roles initially, maintaining total control and use of the assets.

Inter Vivos Efficacy: Unlike a will, the trust is effective immediately. It is a living legal entity. If the Grantor becomes incapacitated, the trust does not stop working; the office of Trustee simply transfers to the named Successor Trustee, ensuring continuity of management without court interference.

The defining feature of a funded living trust is its ability to bypass the probate process entirely.

Legal Theory: When the Grantor dies, they do not technically own the trust assets; the Trust owns them. Since the Trust does not die, there is no need for a probate court to transfer title. The Successor Trustee simply follows the instructions in the trust document to distribute assets or hold them for beneficiaries.

Privacy: Because there is no court case, there is no public file. The trust document remains a private family matter, shielded from public scrutiny.

Speed: Trust administration can begin immediately after death. There is no waiting for "Letters Testamentary." This allows for immediate access to funds for funeral expenses and property maintenance.

The most common point of failure for a living trust is "funding." A trust is like a safe; it offers no protection if the assets are left outside of it. Funding is the process of legally transferring assets from the individual's name to the trust's name.

Real Estate: Requires a new deed (often a Quitclaim Deed) recording the transfer to the trustee.

Financial Accounts: Requires changing the title at the bank or brokerage.

The Pour-Over Will: To mitigate the risk of unfunded assets, a "Pour-Over Will" is drafted alongside the trust. It acts as a safety net, directing any assets left outside the trust to be transferred into it at death. However, assets caught by the Pour-Over Will must go through probate to get to the trust, defeating the primary purpose of avoiding court for those specific items.

To provide a nuanced comparison, one must move beyond definitions to a functional analysis of how these instruments perform in the real world.

The financial difference between wills and trusts is largely a question of timing.

Wills (Pay Later): A will is generally cheaper to draft, often costing between $300 and $1,500. However, the backend costs are high. Probate fees, court costs, and executor commissions can consume 3% to 8% of the estate. For a $1 million estate, this backend cost could exceed $50,000.

Trusts (Pay Now): A trust is more expensive to create, typically ranging from $1,500 to $5,000. It requires more effort to fund. However, the backend administration is significantly cheaper, usually involving only hourly legal advice or professional trustee fees (approx. 1-2%), resulting in substantial net savings for the beneficiaries.

Insight: The trust effectively shifts the cost from the grieving family (post-death) to the planner (pre-death), while typically reducing the total aggregate cost of transmission.

Incapacity: A will offers zero protection for incapacity. If a person relies solely on a will and becomes incompetent, their family must seek a "Living Probate" (Conservatorship/Guardianship), which is public, humiliating, and expensive. A trust handles this privately through the Successor Trustee.

Distribution Logic: Trusts allow for complex distribution schemes (e.g., "hold funds until age 30," "match salary earnings," "special needs provisions"). While wills can create "testamentary trusts" to do this, those trusts remain under court supervision, incurring ongoing fees. Living trusts execute these instructions privately.

In an age of digital exposure, the privacy of the living trust is a premium feature. Probate files list the names and addresses of beneficiaries and the value of their inheritance. This public directory can make heirs targets for fraud. Trusts maintain confidentiality, disclosing information only to those legally entitled to it.

| Feature | Last Will and Testament | Revocable Living Trust |

| Activation Time | At Death | Immediate (Creation) |

| Probate Required? | Yes (Guaranteed) | No (If funded properly) |

| Privacy | Public Record | Private |

| Incapacity Coverage | None (Requires POA) | Full Management by Trustee |

| Cost Structure | Low Upfront / High Backend | High Upfront / Low Backend |

| Guardianship | Yes (Exclusive mechanism) | No |

| Distribution Speed | Slow (Months/Years) | Fast (Weeks/Months) |

| Asset Retitling | Not required during life | Required (Funding) |

The effectiveness of a Living Trust is entirely dependent on funding. An unfunded trust is a "dry trust," offering little more than a paper shell. The most significant asset for most families is their home, and transferring it to a trust requires a specific legal instrument: the Deed.

A Quitclaim Deed is a legal instrument used to transfer interest in real property from a grantor to a grantee. Unlike a Warranty Deed, which guarantees that the title is clear and that the grantor has the right to sell it, a Quitclaim Deed makes no warranties. It essentially states, "I transfer whatever interest I have in this property to you, whether that interest is valid or not".

In the context of trust funding, the Grantor is typically transferring the property from themselves (as an individual) to themselves (as Trustee). Because the parties are effectively the same person, there is no need for the "seller" to warrant the title to the "buyer." The Grantor knows the history of the property. Therefore, the Quitclaim Deed is the standard, most efficient, and cost-effective tool for this transfer.

Process: The deed must include the legal description of the property, the name of the Grantor, and the name of the Trust as the Grantee. It must be signed before a notary and recorded with the county clerk.

Risk Factors: While efficient for trusts, Quitclaim Deeds are risky in sales to strangers because they offer no protection against liens or title defects. However, for the specific purpose of "funding" a trust, this lack of warranty is a feature, not a bug, as it simplifies the transaction.

Some states offer a "Transfer on Death" deed, which functions like a beneficiary designation for a house. While this avoids probate, it lacks the incapacity protection of a trust. If the homeowner becomes incapacitated, the house cannot be sold or refinanced without a conservatorship, whereas a Trustee could manage the property immediately.

The market for estate planning services has evolved significantly, offering consumers various entry points ranging from full-service representation to app-based subscriptions.

The "gold standard" remains the retention of a specialized estate planning attorney.

Retainer Model: Clients pay a retainer or a flat fee (e.g., $2,500 - $5,000) for a comprehensive plan.

Value: The attorney provides legal counsel, not just document drafting. They analyze tax implications, family dynamics (e.g., spendthrift heirs), and ensure the proper execution of documents.

"Attorney on Retainer": Some firms offer ongoing retainer relationships, where the client pays a monthly or annual fee to have the attorney available for questions. This model ensures that the plan evolves with changes in the law or family circumstances.

Services like LegalShield have democratized access to basic estate planning.

Model: For a monthly subscription (e.g., $25-$60), members gain access to provider law firms.

Coverage: Basic plans often include the preparation of a Standard Will, Living Will, and Power of Attorney at no additional cost. Trusts, being more complex, are typically offered at a discount (e.g., 25% off the provider's hourly rate) rather than being fully included.

Critique: Reviews of such services are mixed. While they provide excellent value for simple documents, the "volume" business model may limit the depth of time an attorney can spend on complex planning. Some users report frustration with responsiveness or the quality of referrals for specialized needs.

Niche Evolutions: New entrants like Attorney Shield focus on specific legal verticals, such as immediate representation during police encounters, illustrating the fragmentation and specialization of the "legal app" market.

The lowest cost option is the "Do-It-Yourself" approach using online forms.

Hidden Dangers: Estate planning is highly state-specific. A form that works in Texas might be invalid in Florida due to differences in witness requirements or specific statutory language.

The "Simple" Trap: Users often believe their situation is "simple" and inadvertently create "heir-locked" situations (e.g., leaving money outright to a minor, necessitating court guardianship) that a professional would have avoided. The cost of fixing a bad will in probate often exceeds the cost of hiring an attorney to draft it correctly in the first place.

There is no "one size fits all" solution. The choice between a will and a trust depends on the specific profile of the individual.

Profile: Renters, savings < $100k, minor children.

Recommendation: Will.

Reasoning: The primary need is naming a guardian for the children. With no real estate and limited assets, the probate process may be simplified (small estate affidavit), making the cost of a trust unnecessary. A will is sufficient and cost-effective.

Profile: Owns a primary residence, equity > $150k.

Recommendation: Living Trust.

Reasoning: In many states, owning a home triggers full probate. The cost of probate (e.g., $20k+) vastly outweighs the cost of setting up a trust ($2k). The trust serves as an insurance policy against probate fees.

Profile: Second marriage, children from prior relationships.

Recommendation: Living Trust (with specific sub-trusts).

Reasoning: A simple will leaving everything to the spouse relies on the spouse's honor to provide for the stepchildren. A trust can mandate that the surviving spouse receives income for life, but the principal is preserved for the children of the first marriage. This "dead hand control" is essential for protecting inheritance in blended families.

Profile: Owns an LLC or Corporation.

Recommendation: Living Trust.

Reasoning: A business requires immediate decision-making. If the owner dies, a will requires a court order to appoint an executor to sign payroll checks—a delay that could bankrupt the company. A Trustee can step in immediately to keep the business running.

The distinction between a Last Will and Testament and a Revocable Living Trust is fundamental to the architecture of estate planning. The will is a testamentary instrument—a directive to the probate court that activates only upon death. It is the exclusive vehicle for naming guardians for minor children but carries the burdens of public exposure, statutory delays, and significant court costs. It is, in essence, a "cleanup" tool for those who have not arranged a private transfer mechanism.

The Living Trust, conversely, is an inter vivos entity—a private vessel for asset management that operates continuously through life, incapacity, and death. By severing the legal title from the equitable interest, it bypasses the state’s probate machinery, offering privacy, efficiency, and seamless continuity of control. While it requires a higher upfront investment of time and capital to establish and fund, the long-term economic and emotional benefits for heirs often make it the superior choice for homeowners and those with complex assets.

For the modern family, the question is often not "Will or Trust," but rather how to integrate both. A robust plan typically employs a Living Trust as the primary engine for asset transfer, supported by a "Pour-Over Will" to handle guardianship and act as a safety net. Whether utilizing traditional counsel or modern legal subscription services, the imperative remains the same: to displace the state’s default plan of intestacy with a thoughtful, private design that preserves both wealth and harmony.

To fully appreciate the "Trust Premium" (the higher upfront cost), one must analyze the "Probate Tax" (the backend cost).

California Probate Code § 10810: This statute sets the standard for many fee structures.

4% of the first $100,000

3% of the next $100,000

2% of the next $800,000

1% of the next $9,000,000

Example Calculation: For a widow owning a home worth $1.2 million and savings of $300k (Total $1.5M).

Probate Fees: Attorney: $28,000. Executor: $28,000. Court Costs: ~$2,000. Total: $58,000.

Trust Administration: If the same estate was in a trust, the Successor Trustee (often a family member) might waive a fee or take a reasonable hourly rate. Legal fees for "trust settlement" (not probate) might range from $3,000 to $5,000. Total: ~$5,000.

The Delta: The Trust saves the family over $50,000. This ROI makes the initial $3,000 setup fee negligible.

While death is final, incapacity is indefinite.

Conservatorship: Without a trust, if a person develops dementia, the family must petition for Conservatorship. This involves a court investigator, a court-appointed attorney for the incapacitated person (paid from their funds), and annual accountings to the judge. It is invasive and expensive.

Trust Mechanism: A trust defines incapacity privately (e.g., "written opinion of two physicians"). Once triggered, the Successor Trustee takes over. No judge, no court-appointed attorney, no public record. This protection is often the primary motivator for elderly clients to establish trusts.

Both Wills and Revocable Trusts offer a critical tax benefit: the "Step-Up in Basis."

Mechanism: When a person dies, the tax basis of their assets (what they paid for them) is "stepped up" to the fair market value at the date of death.

Impact: If a person bought a house for $100k and it is worth $1M at death, the heirs can sell it for $1M and pay zero capital gains tax.

Trust Confusion: A common myth is that trusts lose this benefit. This is false for Revocable Trusts. Because the Grantor retains control, the IRS treats the assets as part of the Grantor's estate, preserving the step-up. This distinguishes Revocable Trusts from Irrevocable Trusts, which often remove assets from the estate (and thus the step-up) to save on estate taxes.

The Problem: Standard wills often fail to address digital assets (crypto, social media, cloud photos). If the executor doesn't have the password, the asset is lost. If they do have the password but use it without authorization, they may violate federal computer fraud laws (CFAA).

Trust Solution: A trust can hold "digital property" and specifically authorize the Trustee to access, manage, and distribute these accounts. This includes "Legacy Contact" provisions for platforms like Facebook and Apple, ensuring that digital memories are not deleted or locked away forever.

User reviews of legal services highlight the variance in quality.

Positive Experiences: Often cite "patience," "clarity," and "making a difficult process easy". This reinforces that the primary value of an attorney is emotional assurance and clarity, not just document production.

Negative Experiences: Often relate to "unresponsiveness" or "hidden fees". This suggests that for commodity services (like LegalShield), the client experience depends heavily on the specific provider firm assigned, leading to inconsistency.

Implication: For estate planning, which is a relationship-based service, the cheapest option often results in the lowest satisfaction. The "peace of mind" cited in positive reviews is the true deliverable of the estate planning industry.

Legal Disclaimer: Best Attorney USA is an independent legal directory and information resource. We are not a law firm, and we do not provide legal advice or legal representation. The information on this website should not be taken as a substitute for professional legal counsel.

Review Policy: Attorney reviews and ratings displayed on this site are strictly based on visitor feedback and user-generated content. Best Attorney USA expressly disclaims any liability for the accuracy, completeness, or legality of reviews posted by third parties.