The Colorado AI Act is Live (Feb 2026): Is Your Hiring Software Breaking the Law?

The Colorado AI Act is live (Feb 2026). Is your hiring software compliant? Learn the new rules on algorithmic bias and how to avoid cos...

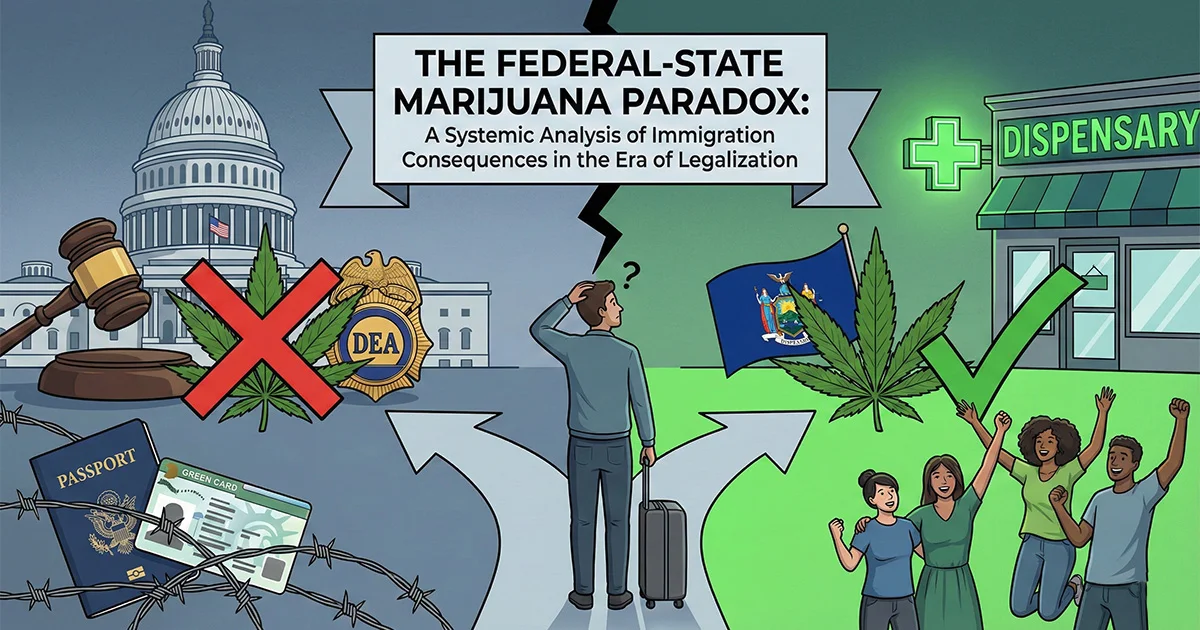

State-legal marijuana poses severe risks for immigrants. Federal law still criminalizes cannabis, threatening green cards and visas with deportation. Navigate the dangerous federal-state paradox.

The question of "why" non-citizens face deportation or inadmissibility for marijuana-related activities—even when those activities are conducted in full compliance with state laws like California’s Proposition 64—requires a deep excavation of the structural collision between American federalism and the doctrine of federal plenary power over immigration. The United States currently operates under a bifurcated legal reality. On one side, a rapidly expanding majority of states have exercised their sovereign police powers to decriminalize, medicalize, or fully legalize the cultivation, distribution, and consumption of cannabis. On the other, the federal government maintains a rigid prohibitionist stance rooted in the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970, which classifies marijuana as a Schedule I narcotic—a substance deemed to have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical utility.

This divergence creates a "trap for the unwary," a legal minefield where the protections of state law dissolve the moment an individual enters the jurisdiction of federal immigration authorities. The "why" is not merely a matter of conflicting statutes; it is a matter of constitutional supremacy. Under the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution, federal law preempts conflicting state laws. While the federal government has largely commandeered its prosecutorial discretion to avoid interfering with state-legal cannabis markets through mechanisms like the Rohrabacher-Farr amendment (which prohibits the Department of Justice from using funds to interfere with state medical marijuana implementations), this discretion does not extend to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) or the administration of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA).

For the non-citizen—whether an undocumented entrant, a visa holder, or a Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR)—the immigration system functions as a strict liability regime regarding controlled substances. The "why" encompasses the mechanics of "admission" versus "conviction," the expansive definition of "illicit trafficking" which now captures legitimate tax-paying employment, and the evolving evidentiary standards that allow border agents to serve as de facto judges of moral character.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of this conflict. It explores the statutory frameworks that mandate these harsh penalties, the specific mechanisms of inadmissibility that function without criminal convictions, the "hemp loophole" defense and its recent judicial narrowing in Matter of Jonalson DOR (2025), and the sociotechnological surveillance state that enforces these rules at the border.

To understand the precarious position of non-citizens in California, one must first deconstruct the two massive statutory bodies that are colliding: the state regulatory framework and the federal prohibition enforcement apparatus.

The foundation of the conflict is the Controlled Substances Act (21 U.S.C. § 802), which places marijuana in Schedule I. This scheduling is the "original sin" of the immigration conflict. Because the INA defines inadmissibility and deportability by referencing the CSA, any substance listed in Section 802 automatically triggers immigration consequences.

The persistence of marijuana in Schedule I means that, for federal purposes, there is no distinction between heroin, LSD, and marijuana. They are legally equivalent in terms of their "dangerousness" and lack of medical utility. When USCIS or an Immigration Judge adjudicates a case, they are bound by this federal schedule. They cannot recognize a "defense" based on state legality because the INA does not contain an exception for conduct that is legal in the jurisdiction where it occurred; it only cares whether the conduct violates the federal standard.

In November 2016, California voters passed Proposition 64, the "Control, Regulate and Tax Adult Use of Marijuana Act." This act fundamentally altered the state's penal code regarding cannabis:

Personal Use: It legalized the possession of up to 28.5 grams of marijuana flower and 8 grams of concentrate for adults 21 and over.

Cultivation: It permitted the personal cultivation of up to six plants per residence.

Commercial Activity: It established a licensing scheme for the commercial production and sale of cannabis.

Retroactive Relief: It allowed for the re-sentencing and destruction of records for prior marijuana convictions.

However, Proposition 64 contained a critical limitation: it could only alter California law. It could not amend the federal CSA or the INA. Consequently, while a non-citizen in California can walk into a dispensary and purchase marijuana without fear of arrest by the Los Angeles Police Department, that same act remains a federal felony under 21 U.S.C. § 844 (simple possession) or 21 U.S.C. § 841 (distribution).

The following table illustrates the stark divergence between the rights granted by California and the penalties imposed by federal immigration law for the exact same conduct.

| Conduct | California Law (Prop 64) | Federal Immigration Law (INA) | Legal Consequence |

| Possession (<30g) |

Legal for adults 21+ |

Conditional bar to GMC; Inadmissible if admitted |

Potential 212(h) waiver available if "single offense" |

| Possession (>30g) | Misdemeanor or Legal (depending on context) |

Controlled Substance Violation (Inadmissible) |

Permanent Bar (No waiver available) |

| Cultivation (6 plants) |

Legal (Personal Use) |

"Manufacture" of Controlled Substance |

Aggravated Felony (if commercial intent inferred) or GMC Bar |

| Dispensary Employment |

Legal, Taxed, Regulated |

"Illicit Trafficking" / "Knowing Aider & Abettor" |

Permanent Inadmissibility (No waiver) |

| Expungement of Conviction |

Record destroyed/sealed |

Conviction remains valid for immigration purposes |

Federal law ignores state "rehabilitative" relief |

This table reveals the structural asymmetry: California grants a "right," but the exercise of that right provides the federal government with the evidence necessary to deny entry or citizenship.

The "why" of deportation is further complicated by the distinction between "inadmissibility" (grounds to keep someone out or deny a green card) and "deportability" (grounds to expel someone already admitted). Marijuana activity triggers both, but in different ways.

The most insidious aspect of the INA regarding marijuana is that a criminal conviction is often unnecessary to destroy a non-citizen's life. Under INA § 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(II), a person is inadmissible if they have been convicted of, or admit having committed, or admit committing acts which constitute the essential elements of a controlled substance violation.

This provision allows a USCIS officer or a consular official to act as prosecutor, judge, and jury. If a non-citizen admits to a medical examiner or an immigration officer that they have used marijuana—even once, and even if it was legal in California—that admission is legally equivalent to a court conviction.

The Scenario: An applicant for a green card attends their medical exam. The doctor asks, "Have you ever used drugs?" The applicant, believing in honesty and protected by state law, says, "Yes, I smoke marijuana occasionally to sleep."

The Consequence: The doctor records this as "Class B" drug abuse or simply notes the admission. This record is forwarded to USCIS. The officer then denies the application based on the admission of the essential elements of a federal crime (possession).

For the admission to be valid, it must meet specific legal standards (the Matter of K- standards): the person must be provided with the definition of the crime and must voluntarily admit to the factual elements. However, in practice, applicants often provide these admissions casually, unaware of the severe ramifications.

The most draconian tool in the federal arsenal is INA § 212(a)(2)(C), known as the "Reason to Believe" (RTB) standard. This section renders inadmissible any alien who the consular officer or Attorney General "knows or has reason to believe" is or has been an illicit trafficker in any controlled substance.

Why is RTB so dangerous?

Standard of Proof: It is significantly lower than "beyond a reasonable doubt." It is akin to "probable cause" or even less. A mere suspicion supported by some evidence is sufficient.

No Conviction Required: An individual who was arrested for drug sales but had the charges dropped due to lack of evidence can still be found inadmissible under RTB if the immigration officer believes the police report over the dismissal.

Guilt by Association: The statute extends to any "knowing aider, abettor, assister, conspirator, or colluder." This captures spouses and business partners of those involved in the industry.

No Waiver: unlike simple possession, there is absolutely no waiver available for an RTB finding. It is a permanent lifetime ban from the United States.

Beyond criminal grounds, INA § 212(a)(1)(A)(iv) renders inadmissible anyone determined to be a "drug abuser or addict".

Mechanism: This determination is typically made by the Civil Surgeon during the mandatory immigration medical exam.

Current Use: The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) technical instructions define "drug abuse" broadly. While the DSM-5 criteria are used, the mere non-medical use of a controlled substance (defined federally) can lead to a classification of "abuse" if it occurred within the last 12 months.

Remission: To overcome this, an applicant must be in "remission," which typically requires 12 months of sobriety. However, a finding of drug abuse creates a significant delay and a permanent mark on the immigration file.

A significant driver of the current crisis is the economic legitimization of cannabis. The cannabis industry is a multi-billion dollar sector in California, generating tax revenue and creating thousands of jobs. For the average worker, a job at a dispensary appears no different than a job at a winery or a pharmacy. The "why" here is the disconnect between labor law and immigration law.

Federal immigration authorities view employment in the state-legal cannabis industry as active participation in a criminal enterprise. Under the INA, "trafficking" does not require violence or cartels; it essentially means the commercial exchange of a controlled substance. Therefore, a "budtender" who sells marijuana to a customer is, in the eyes of federal law, distributing a Schedule I narcotic.

The Ancillary Personnel Problem: The "Reason to Believe" standard extends to "aiders and abettors." This places ancillary workers at risk:

Accountants/Bookkeepers: Managing the finances of a cannabis business.

Security Guards: Protecting the premises of a grow operation.

HR Professionals: Hiring staff for a dispensary. All of these roles "assist" the trafficking operation. USCIS has explicitly stated that employment in the cannabis industry acts as a conditional bar to Good Moral Character.

Snippet highlights the case of Maria Reimers, a green card holder in Washington State (which has similar laws to California). She co-owned a licensed cannabis shop with her U.S. citizen husband. When she applied for naturalization, her application was denied. USCIS cited her business ownership as "illicit drug trafficking."

Implication: Despite paying state taxes and following all state regulations, her "legal" livelihood was the sole evidence used to deny her citizenship. Had she been undocumented, this same evidence could have triggered removal proceedings.

The risk extends to investors. A non-citizen who invests in a cannabis REIT (Real Estate Investment Trust) or a cannabis-focused ETF might be scrutinized. While passive investment is less likely to trigger a "trafficking" finding than direct employment, the broad language of "colluder" or "assister" in INA § 212(a)(2)(C) leaves this open to the interpretation of aggressive consular officers.

As federal enforcement remains rigid, immigration defense attorneys have turned to highly technical legal arguments to protect their clients. The most prominent of these is the "Categorical Approach" and the "Hemp Defense."

The categorical approach is a rigid analytical framework mandated by the Supreme Court (e.g., in Taylor, Mathis, Descamps) to determine if a state conviction triggers a federal immigration consequence.

The Test: Adjudicators must compare the elements of the state statute of conviction to the generic federal definition of the offense. They must not look at the underlying facts (what the person actually did).

The Mismatch: If the state statute is "overbroad"—meaning it criminalizes conduct that the federal statute does not—then there is no "categorical match," and the conviction cannot be a basis for removal.

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (the "2018 Farm Bill") removed "hemp" (cannabis with THC) from the federal definition of marijuana in the CSA.

The Defense: Defense attorneys argue that California's definition of "cannabis" (e.g., in Health & Safety Code § 11359) is broader than the new federal definition because California regulates all cannabis, whereas the federal government now only prohibits marijuana (high-THC cannabis).

The Logic: Since a person could theoretically be convicted in California for possessing a plant that is actually federal "hemp," the state statute is overbroad. Therefore, a California conviction should not trigger deportation.

The legal viability of the hemp defense has recently faced a severe setback. In Matter of Jonalson DOR (March 18, 2025), the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) and the First Circuit Court of Appeals addressed the "time of conviction" rule.

The Case: Jonalson Dor was convicted of marijuana possession in 2018 before the Farm Bill was enacted. He argued that because hemp was legal at the time of his removal hearing, the federal definition should be applied contemporaneously, making his conviction overbroad.

The Ruling: The BIA and First Circuit rejected this. They held that the relevant federal drug schedule is the one in effect at the time of the conviction, not the time of the immigration hearing.

Reasoning: The court emphasized "consistency and predictability," arguing that immigration consequences should attach to the "actual conduct and culpability" at the moment the crime was committed.

Impact: This means that for non-citizens convicted of marijuana offenses before December 20, 2018 (the Farm Bill enactment), the hemp defense is largely dead. Their convictions are compared to the old federal schedule where hemp was illegal. However, for convictions occurring after 2018, the argument remains viable in circuits that haven't ruled otherwise, though the Jonalson DOR precedent is a heavy weight against it.

Ninth Circuit Nuance: In California (9th Circuit), the law is still grappling with these definitions. The 9th Circuit has historically been rigorous in applying the categorical approach, but recent decisions suggest a tightening alignment with the BIA's "time of conviction" rule.

The conflict is not limited to courtrooms; it is enforced at the physical and digital borders of the United States. The "why" of inadmissibility is increasingly found in the digital footprints of non-citizens.

The Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches and seizures is significantly weakened at the border. Under the "border search exception," CBP officers can search electronic devices (phones, laptops) without a warrant.

Scope: CBP Directive 3340-049B allows for "basic" searches (manual scrolling) without any suspicion and "advanced" searches (forensic downloading) with "reasonable suspicion".

The Trap: A traveler returning from abroad might be asked to unlock their phone. If the officer finds text messages discussing marijuana, photos of the traveler at a dispensary, or apps related to cannabis culture (e.g., Weedmaps), this evidence can be used to establish a "reason to believe" the person is a trafficker or drug abuser.

DHS and ICE have implemented pilot programs and policies to monitor the social media accounts of visa applicants and immigrants.

The Risk: Posting a photo of a "legal" purchase in California on Instagram can be flagged. Even if the post is years old, it can be dredged up during a visa renewal or naturalization interview to prove "bad moral character" or admission of a crime.

The Reddit threads analyzed provide qualitative evidence of administrative penalties. Global Entry and NEXUS are discretionary privileges, not rights.

Revocation: Users report having their Global Entry revoked immediately upon admitting to past marijuana use during an interview, or after being found with small amounts of paraphernalia.

The "Script" Failure: In snippet , a user describes how his wife was asked "Have you ever used pot?" She answered honestly ("Yes"), believing state legality protected her. She was denied. This illustrates the critical failure of the "honesty is the best policy" heuristic when facing federal agents. The correct legal strategy—silence—is counter-intuitive to most law-abiding residents.

Immigration attorneys emphasize that the interaction at the border is a legal interrogation. The "Why" of many deportations is simply that the non-citizen spoke when they should have remained silent.

Right to Silence: Non-citizens have a right to remain silent, though this may lead to prolonged detention or denial of entry (for non-LPRs). However, admitting to the elements of a crime is irrevocable.

The Attorney's Advice: "Don't lie, but don't confess." If asked about marijuana, the recommended response is to refuse to answer and ask for a lawyer. This stops the "admission" from being recorded.

When the trap snaps shut, the options for relief are starkly limited. The legal framework is designed to be unforgiving toward controlled substance violations.

The only waiver available for a controlled substance ground of inadmissibility is under INA § 212(h).

Strict Criteria: It is available only for a "single offense of simple possession of 30 grams or less of marijuana".

The Limitations:

Quantity: 31 grams? No waiver.

Type: Hashish or concentrates? Often considered separate from "marijuana" in some jurisdictions or treated more harshly.

Frequency: Two convictions? No waiver.

Context: Possession with intent to sell? No waiver.

Paraphernalia: If the conviction is for paraphernalia, the record must prove it was related only to marijuana (specifically <30g). If the record is ambiguous (could be for cocaine), the waiver is denied.

Hardship: Even if eligible, the applicant must prove "extreme hardship" to a qualifying U.S. citizen relative.

Because federal law ignores state "expungements" that are based on rehabilitation (like completing probation), attorneys must use specific PCR statutes that attack the validity of the original conviction.

California PC 1473.7: This statute allows a person to vacate a conviction if they can show they failed to meaningfully understand the immigration consequences at the time of their plea. This is considered a "substantive defect" and is generally respected by immigration courts (unlike a simple expungement).

President Biden's October 2022 pardon of federal marijuana possession offenses was largely symbolic for non-citizens.

It only applied to federal convictions (D.C. and Federal Court), whereas most marijuana offenses are state convictions.

It did not amend the INA. Therefore, an admission of the conduct underlying a pardoned offense could theoretically still be used, although the pardon itself removes the conviction.

It explicitly did not apply to non-citizens who were not LPRs at the time of the offense.

The "why" of the California-Federal marijuana conflict is a story of a legal system at war with itself. The voters of California have declared that cannabis is a lawful product, a legitimate medicine, and a valid industry. The federal government, through the INA, views it as a moral failing and a criminal enterprise.

Non-citizens are caught in the crossfire of this jurisdictional battle. The mechanisms of their exclusion are vast and overlapping:

Statutory rigidity: The CSA's Schedule I status locks in penalties that are immune to state reform.

Evidentiary looseness: The "Reason to Believe" and "Admission" standards allow for life-altering penalties without the procedural safeguards of a criminal trial.

Economic entrapment: The normalization of the cannabis industry lures non-citizens into employment that federal law defines as trafficking.

Technological surveillance: The digitization of borders means that a single text message or social media post can serve as the smoking gun.

Until Congress amends the INA to create an exception for state-compliant cannabis activity, or until marijuana is descheduled (not just rescheduled) and that change is made retroactive, the "marijuana trap" remains one of the most significant threats to the security of immigrant communities in the United States. The advice from the legal community remains uniform and stark: for the non-citizen, marijuana is never legal.

The analysis indicates that the friction is not merely a "conflict of laws" but a "conflict of realities," where the lived experience of California residents is fundamentally incompatible with the statutory requirements of federal immigration status.

Legal Disclaimer: Best Attorney USA is an independent legal directory and information resource. We are not a law firm, and we do not provide legal advice or legal representation. The information on this website should not be taken as a substitute for professional legal counsel.

Review Policy: Attorney reviews and ratings displayed on this site are strictly based on visitor feedback and user-generated content. Best Attorney USA expressly disclaims any liability for the accuracy, completeness, or legality of reviews posted by third parties.